Do We Do This Here? / Marking Camp David

Originally coined Shangri-La after the paradise in James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon, Camp David exists today as a naval support facility and secure corporate-style retreat for diplomatic proceedings seeped in sociopolitical protocols where the image of the president in his natural habitat is reproduced against the background of the material presence of Catoctin Mountain Park. Historically, Camp David’s walls have not been literal borders, but instead are embodied in the thick space of this National Park, located 60 miles north, northwest of Washington D.C.

From a secret refuge for FDR to a training facility for the Office of Strategic Services during World War II, the state and relevance of Camp David under our current president lies in question. The dissolution of the use of the camp as a presidential retreat, and subsequent inclusion as a historic place on the National Register through its presentation as part of the cultural landscape of Catoctin Mountain Park seems immanent. What would it mean for the place of the president, one of the most influential figures in our cultural imagination, to become part of the National Park System’s construction of authenticity, promoting a specific understanding of America’s cultural heritage.

In its active state as a site for Presidential activities, the camp is charged in such a way that perpetuates a discord between camp and park—a discord that reveals the material medium and visual rhetoric as such. As the current camp becomes a historic site and is stripped of its symbolic power, the risk of concealing that fissure and promoting the use of the natural environment for the nationalistic production of a place-based myth is reinforced—becoming the ultimate stable representation of and for America - locking us into a present past.

Rather than attempting to counter one myth with another, Do We Do This Here? seeks to utilize the mark as a method of engaging the material medium and visual rhetoric which create the physical place and ongoing cultural mythology of Camp David. By calling attention towards, creating distinction from, and framing in relationship to, this project uses the mark for its capacity to show seeing. The marks are notations, pre-architectural programs, and proposals for built architectural forms, all which seek to register the presence of codes and material techniques that already construct this myth. In doing so, the intention is to reveal a more public, less codified way of occupying the thick wall of paradise. To see a place rather than to read a place, is to mark what is hiding in plain sight.

Do We Do This Here? takes on the hypothetical task of listing Camp David as a Historic Place on the National Register, imagining an architectural engagement with the physical documents, their contents, and the context they produce, marking a new sense of place which claims no single authenticity. By emphasizing the importance of the wall in the construction of paradise, the milieu within which Camp David thrives, the opportunity is opened to bring progress to our collective American identity as Natures Nation. Isolated in the authenticity of the past, the project gives a hopeful view of the future cultural role and physical presence of the camp.

-

Excerpts from the registration package for President Hover’s Camp Rapadian

Marked excerpts from the proposed registration package for Camp David

Exhibition / presentation, immersive environment framed by fictions past and future

The project as exhibited was framed on two sides by two projections. The first was the film Lost Horizon directed by Frank Capra of which the orientalist paradise served as the namesake for the original name of Camp David, Shangri-La. A fiction, it can be understood as a contextual frame for understanding the cultural role of the Camp in its conception. The second was sliding footage of the current contemporary context of Camp David, the frame within which the physical presence of the camp can be understood.

Registration Section 1: Images / Documents

The images of the camp are perhaps the most important of these documents, as they are the picturesque medium through which we as a public contextualize the goings-on of a place we cannot physically access. Through them, we can see the use of the camp by the 12 presidents following FDR, not including our current President.

Through the process of reverse “blotting”, the collected public images of the camp are marked to revealing the general relationships between built form, inhabitation, and the scenic representation of an idealized landscape. From those blots, an embodied space is proposed as a first attempt at spatializing the general relationships in the image.

Registration Section 2: Physical Site

Camp David sits within Catoctin Mountain Park. The trajectory through the park and towards the camp, the boundary of the camp, and the interior of the camp, are taken as three distinct areas upon which spatial marks can begin to be made in the documentation process of the Camp for the National Register.

BOUNDARY

The boundary of the camp in its state as a presidential retreat is kept, creating clearing and public promenade around the camp. A row of evergreen saplings is planted, marking the camp’s physical expression of its non-physical border. The interior is engaged through two excavations / extensions into the surrounding park landscape. Each structure highlights current ways in which the rhetoric of the national park obscures the myth making of the camp.

INTERIOR

The boundary clearing holds the interior of the camp, which is divided into two areas along a central axis. The left most is the Naval Support Facility and the right most is the presidents residence and other supporting camp structures and places of recreation. As the camp becomes integrated into the park, the clearing is drawn inward at two moments, presenting the dichotomous yet uniquely dependent faces of this singular program.

On the right side of the camp, a number of cabins and recreation facilities are clustered around Aspen Lodge, the President’s cabin, which includes a swimming pool, golf course, bunker, and doghouse. Sketched by FDR himself, the cabin is designed around a view that extends one’s gaze over the national park. With sitting presidents no longer gracing the Park with their gaze, a promontory reaches out as the physical extension of the scenic view—it fills the frame of FDR’s picture window with a publically occupied space. Rather than offering the typical national park scenic overlook, self-evident in its function, meaning, and purpose, the promontory draws viewers into the mediating device by radically extending the single axial view over the course of its length, and then turning inwards, framing a tight view of other viewers.

On the left side of the camp, we have the other face of Camp David-- the infrastructure of NAVTHURPACC, or naval support facility Thurmot. Though in discord with the usual vernacular of park structures, the imposing presence of the buildings on this side of camp have historically used the national park’s capacity for concealment to efface their own legibility. For example, in an effort to conceal the presence of a military command center during the visit of Nikita Khrushchev in 1959, the same visit within which the list of Western films was proposed, signage and an observation deck were added to reinforce the perception that the structure housing the command center was in fact a water tower. Like other forms of media in contemporary culture, where audiences are encouraged to look through instead of at, the act of effacing the legibility of the water tower by using it as a scenic overlook re-enforced its capacity to “hide in plain sight”: there for all to see, but its very function making it see-through.

TRAJECTORY

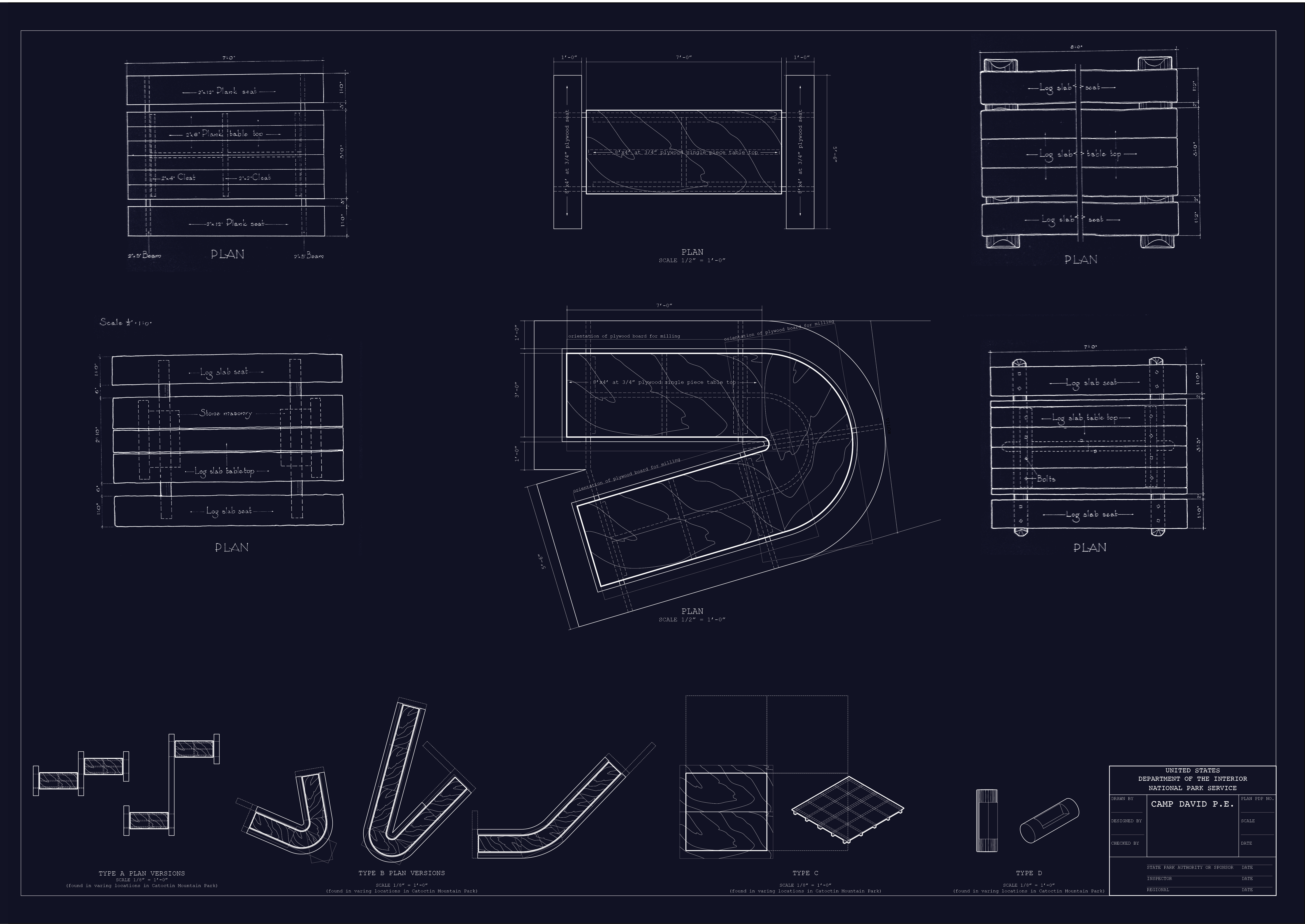

The trajectory towards the camp, just like the entry into paradise, is an important part of the construction of the myth. A flowershop and picnic pavilion are proposed, flanking the entrance to the camp along Park Central Road. Both mark through juxtaposition of program or material type, bringing something from outside into the park and thus questioning the constructedness of the environment itself.

This project was completed at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design in 2017 for satisfaction of the Masters of Architecture Thesis, advised by Silvia Benedito.

It was nominated for the James Tempelton Kelley Thesis Prize and for publication in Harvard Graduate School of Design's Platform 10 Annual Journal.